This article is created by The Better India and sponsored by WingifyEarth

A peek into the vision behind the historic Krushi Bhavan in Odisha, and how it combines traditional wisdom, craftsmanship, and sustainability with modern elements to create groundbreaking architecture.

Krushi Bhawan in Odisha is one of the finest examples of sustainable architecture in India. Spread over 1.3 lakh square feet and four floors, it was envisioned by Chief Minister Naveen Patnaik as the office of the State Department for Agriculture and Farmers’ Empowerment in Bhubaneswar, which was designated a smart city in 2016.

Delhi-based architecture firm Studio Lotus, which adopts the principle of conscious design and use of local resources, was responsible for executing the project at a cost of Rs 70 crore.

The vision behind Krushi Bhavan’s creation

Krushi Bhavan was initially envisaged as a government facility to hold the directorate offices and adjunct workspaces. However, the plan was then revised to create an invigorated urban realm.

The architecture was inspired by German architect Otto Königsberger‘s original vision for Bhubaneswar, where he saw the Capitol Complex with a host of government offices becoming a congregation point for the public as well.

Congruent with the project objective, the ground floor comprises a learning centre, a gallery, an auditorium, a library, and training rooms. Similarly, the rooftop has been designed to house urban farming exhibits and demonstration of agricultural best practices.

Studio Lotus also suggested that the building should also be able to host public functions and become a gathering center for the local community, and the government willingly embraced the idea.

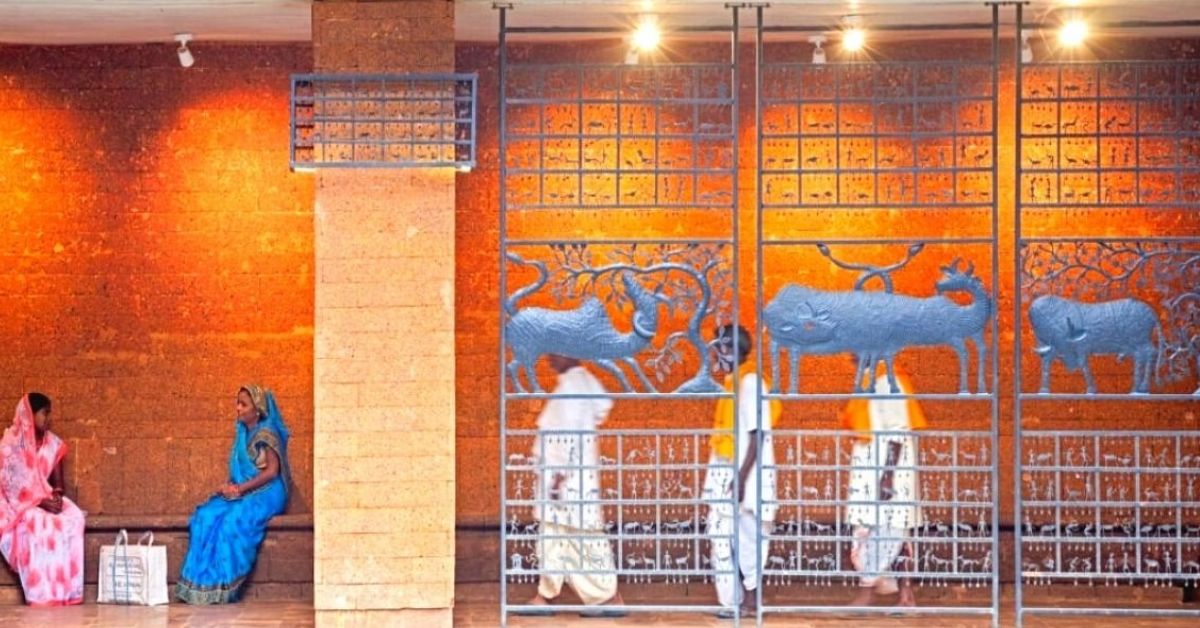

This was achieved by opening up the ground floor as an extension of the street and raising it on stilts to create a public plaza that could be utilised for community engagement through workshops, training modules, and conferences dedicated to the best farming practices for the state.

The project also promotes sensitisation to local materials and looks at a new way of integrating craft in a contemporary environment. The material palette uses a combination of exposed brick and local stones like laterite and khondalite, and by adapting local motifs to an unprecedented architectural scale, Krushi Bhawan emerges as an example of how the government can serve as the prime patron of regional crafts. The Public Plaza boasts of greenery and is home to a garden filled with native flora, featuring an informal amphitheatre and a pond that cools the forecourt.

The building uses passive design strategies in the staggered massing (that helps shield the building from the heat of the sun), the recessed windows, and the double-skin brick facade.

To address the tropical climate, a night-purge ventilation system — a first in an office building in Odisha — takes advantage of the structure’s optimal north–south orientation, with 40 mechanised rooftop ventilators extracting hot air and injecting the cooler night air through ceiling and floor vents.

Only 20 percent of the interior spaces are air-conditioned — the third-floor offices that become extremely uncomfortable for a brief period each year. The raised plaza, the courtyard, and light wells all enhance air circulation. Other sustainable aspects of the project are solar panels on the roof, rainwater harvesting, and the extensive use of local materials.

‘A collaborative process’

For the project, Sidhartha Talwar, design principal at Studio Lotus, won the JK Architect Award of the Year in 2020. “The concerns of sustainability, cultural and contextual suitability and stakeholder empowerment apply to each project, regardless of who commissioned it or what the budget shapes up to be,” he notes.

The team at Studio Lotus

But the key difference between a private and public project, he explains, is determined by the end user — private projects are essentially geared towards objective fulfilment for a small or well-defined subset, be it a retail outlet, a boutique hotel, or a small private residence. Public projects, on the other hand, must be inclusive, agile, and adaptable within their immediate urban setting, so as to remain relevant and useful for the community in the years to come.

“For us, the project and its stakeholders determine the material and technology that goes into the making of a building,” says Talwar. “We strive to produce designs that serve as solutions to a set of pertinent questions, rather than as products of a creative exercise. The solutions that emerge are a direct result of stakeholder engagement, a collaborative process from start to end.”

The project also promotes sensitisation to local materials and looks at a new way of integrating craft in a contemporary environment.

Krushi Bhavan was voted as a ‘Highly Commendable in Office Building Category’ at the World Architecture Festival in 2019 and was the ‘Supreme Winner in Public Building’ category at the Surface Design Award London.

Leave A Comment

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked.