This article is created by The Better India and sponsored by WingifyEarth

Bengaluru startup Uravu Labs, the brainchild of four engineers, has developed a working prototype that can produce water using 100% renewable energy.

Even as batchmates at the National Institute of Technology (NIT), Calicut, Swapnil Shrivastav (28) and Venkatesh R (27) were heavily focused on technology-driven sustainability. Having worked on personal projects of rainwater harvesting and wastewater treatment, they felt that water is one of the most neglected domains in the country.

“Back then, the last great innovation of reverse osmosis had happened during the 1960s, and even that ended up wasting more water than it purified. We keep saying that India is a rain-fed country, but about 80 per cent of our drinking water requirements come from groundwater,” Swapnil tells The Better India.

As per a report by the Comptroller and Auditor General of India released last month, the overall stage of groundwater extraction had increased from 58 per cent to 63 per cent between 2004 and 2017.

“So right after graduation in 2016, we started exploring the ‘water from air’ concept and came up with a traditional electricity-based atmospheric water generator (AWG) in 2018. But we had a vision of developing technology that could provide high-quality drinking water to serve as a viable alternative to groundwater, with completely renewable energy sources,” he says.

In 2019, the duo joined hands with Pardeep Garg (34), a graduate of Bengaluru’s Indian Institute of Science and the Massachusetts Institute of Technology; and Govinda Balaji (30), from Coimbatore Institute of Technology, to establish their water-tech startup Uravu Labs. After a year spent researching, funded by a 50,000 USD grant by Water Abundance XPrize, their efforts came to fruition when they developed a working prototype that could produce five litres of water per day (LPD) in a wholly sustainable manner.

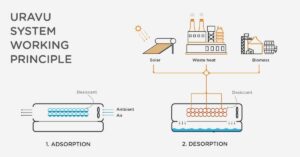

Occupying an area of 2 square meter, the Uravu AWG is a thermal and desiccant-based system that makes use of absorption and desorption processes to convert ambient air into drinking water, priced at Rs 5 per litre.

“During the adsorption process, air is passed over a desiccant core made of silica gel, which has a very high affinity for water vapour. So with a standard desiccant using 10 kg of silica gel, as many as 2 litres of water can be adsorbed within three hours. The desorption process also lasts for another three hours, during which solar heat is used to release the vapour back. The moisture can then be condensed into completely renewable drinking water,” Swapnil explains.

“So each cycle lasts about six hours and is repeated four times during 24 hours. We use a thermal battery which enables the desorption process during nighttime,” he says.

Swapnil says the quality of the water produced by Uravu AWGs fits the parameters set by the International Organization for Standardization (ISO) and the World Health Organization (WHO). The National Accreditation Board for Testing and Calibration Laboratories (NABL) has also approved it for drinking usage.

While the startup hasn’t made any commercial sales, he adds, it has secured three pilot projects for a real-estate developer, a beverage manufacturer, and a corporate office.

Source: Swapnil Shrivastav

Strategic Advantage

Swapnil says that while several companies occupy a space in the Indian AWG market, they primarily use air-conditioning-based technology that employs high levels of energy.

“These machines are non-renewable, and you’ll hardly get three litres of water for one unit of electricity. Even if one pairs it with a solar PV system, you’ll have to use electronic supply batteries that end up almost doubling the cost of the operation,” he notes.

“At Uravu, we decoupled the desiccant and heat systems, which gives us the strategic advantage of not being limited to solar energy, but tapping into any heat source to produce renewable water,” he says.

He explains, “So a processing, textile or chemical industry could ideally use their existing waste heat, even produced while burning biomass, to power our AWGs and fulfil their on-site drinking water requirements. Another application we’re looking at is breweries, which have a wet by-product called ‘beer spent grain’. This can be dried using exhaust air, which enhances the humidity of the air, and the dried BSG can be burnt to generate heat for the AWG. So we can utilise the waste generated at the brewery and enable a circular system to continually produce water.”

Swapnil says the Uravu AWG can even function in areas with as low as 30 percent relative humidity (RH).

“Our focus is on designing custom desiccant systems relevant to the weather conditions of a site. So in an area with 80 per cent RH, say Chennai, about 20 kg of silica gel will be used to generate 20 litres of water. But in Rajasthan, where you usually have 30 to 40 per cent of RH, the amount of silica gel will be four times higher. What’s more, silica gel contributes to only 20 per cent of the AWG’s total cost, so we can supply water to less humid areas without a marginal increase in price,” he says.

Road Map

Swapnil notes that the startup’s primary focus lies in reducing the reliance on groundwater by the Indian beverage manufacturing industry.

“Globally, the beverage industry consumes 1,500 billion litres of water every year, and about 45 per cent of this amount is sourced from groundwater. This includes manufacturers of packaged drinking water, cold drinks, energy drinks, and alcoholic beverages like beer and wine. This is equivalent to almost 20 percent of the entire world’s drinking requirements,” he claims.

“In India, such companies typically look for areas with a sufficient water table or set up a factory near an existing spring. We refer to groundwater as a non-renewable resource because it has accumulated for billions of years and takes a drastically long time to recharge naturally. For instance, a factory could be set up in an area where the groundwater would be completely depleted within the next ten years. On the other hand, air is replenished in eight to 10 days and makes for a much more renewable source to generate water,” he says.

He says that Uravu’s initial launches will involve AWGs with 20 and 100 LPD capacities, targeted at the real estate sector target market, including educational and office campuses, luxury hospitality units, and residential areas in a limited capacity.

“A 20 LPD rooftop unit would be enough to fulfill the drinking and cooking needs of a family of five. But we can only look at residents of low-rise buildings and independent houses,” he notes.

Beverage manufacturers, however, would require AWGs with 2,000 LPD capacities, and the scaling of operations would help reduce the price of renewable water by Rs 1.5, he adds.

Swapnil says Uravu Labs is also looking to fulfill projects for ‘strategic partners’ such as the World Bank and the Ministry of Jal Shakti, which would enable them to fulfill the drinking requirements in the rural and remote areas of the country.

“The residents of such areas wouldn’t have the purchasing power to buy AWGs, but we can help subside them through governmental initiatives. One comes across multiple reports of women travelling a couple of hours daily to procure drinking water for their households. With in-house AWGs, they could use the same hours on their primary economic activities,” he says.

“For the next few years, our roadmap involves fulfilling B2B orders for green projects, helping create impact in terms of both preventing groundwater depletion and helping local communities preserve their water for themselves,” he says.

Leave A Comment

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked.